МАРК РЕГНЕРУС ДОСЛІДЖЕННЯ: Наскільки відрізняються діти, які виросли в одностатевих союзах

РЕЗОЛЮЦІЯ: Громадського обговорення навчальної програми статевого виховання

ЧОМУ ФОНД ОЛЕНИ ПІНЧУК І МОЗ УКРАЇНИ ПРОПАГУЮТЬ "СЕКСУАЛЬНІ УРОКИ"

ЕКЗИСТЕНЦІЙНО-ПСИХОЛОГІЧНІ ОСНОВИ ПОРУШЕННЯ СТАТЕВОЇ ІДЕНТИЧНОСТІ ПІДЛІТКІВ

Батьківський, громадянський рух в Україні закликає МОН зупинити тотальну сексуалізацію дітей і підлітків

Відкрите звернення Міністру освіти й науки України - Гриневич Лілії Михайлівні

Представництво українського жіноцтва в ООН: низький рівень культури спілкування в соціальних мережах

Гендерна антидискримінаційна експертиза може зробити нас моральними рабами

ЛІВИЙ МАРКСИЗМ У НОВИХ ПІДРУЧНИКАХ ДЛЯ ШКОЛЯРІВ

ВІДКРИТА ЗАЯВА на підтримку позиції Ганни Турчинової та права кожної людини на свободу думки, світогляду та вираження поглядів

РЕЗОЛЮЦІЯ: Громадського обговорення навчальної програми статевого виховання

ЧОМУ ФОНД ОЛЕНИ ПІНЧУК І МОЗ УКРАЇНИ ПРОПАГУЮТЬ "СЕКСУАЛЬНІ УРОКИ"

ЕКЗИСТЕНЦІЙНО-ПСИХОЛОГІЧНІ ОСНОВИ ПОРУШЕННЯ СТАТЕВОЇ ІДЕНТИЧНОСТІ ПІДЛІТКІВ

Батьківський, громадянський рух в Україні закликає МОН зупинити тотальну сексуалізацію дітей і підлітків

Відкрите звернення Міністру освіти й науки України - Гриневич Лілії Михайлівні

Представництво українського жіноцтва в ООН: низький рівень культури спілкування в соціальних мережах

Гендерна антидискримінаційна експертиза може зробити нас моральними рабами

ЛІВИЙ МАРКСИЗМ У НОВИХ ПІДРУЧНИКАХ ДЛЯ ШКОЛЯРІВ

ВІДКРИТА ЗАЯВА на підтримку позиції Ганни Турчинової та права кожної людини на свободу думки, світогляду та вираження поглядів

Контакти

- Гідрологія і Гідрометрія

- Господарське право

- Економіка будівництва

- Економіка природокористування

- Економічна теорія

- Земельне право

- Історія України

- Кримінально виконавче право

- Медична радіологія

- Методи аналізу

- Міжнародне приватне право

- Міжнародний маркетинг

- Основи екології

- Предмет Політологія

- Соціальне страхування

- Технічні засоби організації дорожнього руху

- Товарознавство продовольчих товарів

Тлумачний словник

Авто

Автоматизація

Архітектура

Астрономія

Аудит

Біологія

Будівництво

Бухгалтерія

Винахідництво

Виробництво

Військова справа

Генетика

Географія

Геологія

Господарство

Держава

Дім

Екологія

Економетрика

Економіка

Електроніка

Журналістика та ЗМІ

Зв'язок

Іноземні мови

Інформатика

Історія

Комп'ютери

Креслення

Кулінарія

Культура

Лексикологія

Література

Логіка

Маркетинг

Математика

Машинобудування

Медицина

Менеджмент

Метали і Зварювання

Механіка

Мистецтво

Музика

Населення

Освіта

Охорона безпеки життя

Охорона Праці

Педагогіка

Політика

Право

Програмування

Промисловість

Психологія

Радіо

Регилия

Соціологія

Спорт

Стандартизація

Технології

Торгівля

Туризм

Фізика

Фізіологія

Філософія

Фінанси

Хімія

Юриспунденкция

A GOOD MOVE TO MASTER MATHS

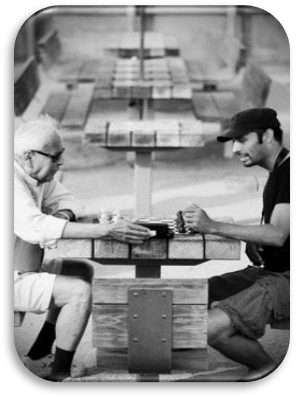

In the spirit of the current world championship bout between Norwegian grandmaster Magnus Carlsen and Indian grandmaster Viswanathan Anand, we should seriously consider the role of chess in how young students learn mathematics.

In the spirit of the current world championship bout between Norwegian grandmaster Magnus Carlsen and Indian grandmaster Viswanathan Anand, we should seriously consider the role of chess in how young students learn mathematics.

The two activities have plenty in common. In either, one’s success relies strongly on the ability to be creative under some set of rules.

Beginners in both maths and chess seem to play only for the rules, for they don’t really understand much else yet. In maths, this means swinging the algebraic sword blindly in the hope of making progress. In chess, making any legal move is enough for a beginner, so long as their piece can’t be immediately taken.

Playing either game this way seems fine at first, for if the teacher has the right experience then the newbie will be punished or rewarded accordingly, and will shape their ideas and strategy for the next time around.

However, while chess has maintained huge popularity worldwide, the allure of doing maths seems lower than ever.

And if we think about the reasons for which we bellow the importance of maths – critical thinking, decision making, mental agility – it seems surprising that chess isn’t routinely taught in maths classrooms across the country.

And if we think about the reasons for which we bellow the importance of maths – critical thinking, decision making, mental agility – it seems surprising that chess isn’t routinely taught in maths classrooms across the country.

Learning chess could actually have a two-fold effect. Not only could we impart the aforementioned skills through something, which more people seem to enjoy, but also we might able to transition students to maths through chess.

Students of chess use symbolic notation to record their moves, arithmetic to add up their points and creativity to win position and pieces. And plenty of new ideas in maths could be first taught under the framework of chess.

TEXT 9

Читайте також:

- And pulling Dumbledore’s uninjured arm around his shoulders, Harry guided his headmaster back around the lake, bearing most of his weight.

- CANDIDATE'S AND MASTER'S PROGRAMS AT NSTU

- Harry found his voice was shaking, as were his knees. He moved over to a desk and sat down on it, trying to master himself.

- MASTERING ECONOMICS

- My Memories and Miseries As a Schoolmaster

- Section III. Texts for Masters

- The Daily Prophet, however, has unearthed worrying facts about Harry Potter that Albus Dumbledore, Headmaster of Hogwarts, has carefully concealed from the wizarding public.

- THE POTIONS MASTER

- WOMEN IN MATHS

- Програма Language Master

| <== попередня сторінка | | | наступна сторінка ==> |

| New methods for old problems | | | A BRIEF HISTORY OF NUMBERS AND COUNTING |

|

Не знайшли потрібну інформацію? Скористайтесь пошуком google: |

© studopedia.com.ua При використанні або копіюванні матеріалів пряме посилання на сайт обов'язкове. |