РЕЗОЛЮЦІЯ: Громадського обговорення навчальної програми статевого виховання

ЧОМУ ФОНД ОЛЕНИ ПІНЧУК І МОЗ УКРАЇНИ ПРОПАГУЮТЬ "СЕКСУАЛЬНІ УРОКИ"

ЕКЗИСТЕНЦІЙНО-ПСИХОЛОГІЧНІ ОСНОВИ ПОРУШЕННЯ СТАТЕВОЇ ІДЕНТИЧНОСТІ ПІДЛІТКІВ

Батьківський, громадянський рух в Україні закликає МОН зупинити тотальну сексуалізацію дітей і підлітків

Відкрите звернення Міністру освіти й науки України - Гриневич Лілії Михайлівні

Представництво українського жіноцтва в ООН: низький рівень культури спілкування в соціальних мережах

Гендерна антидискримінаційна експертиза може зробити нас моральними рабами

ЛІВИЙ МАРКСИЗМ У НОВИХ ПІДРУЧНИКАХ ДЛЯ ШКОЛЯРІВ

ВІДКРИТА ЗАЯВА на підтримку позиції Ганни Турчинової та права кожної людини на свободу думки, світогляду та вираження поглядів

- Гідрологія і Гідрометрія

- Господарське право

- Економіка будівництва

- Економіка природокористування

- Економічна теорія

- Земельне право

- Історія України

- Кримінально виконавче право

- Медична радіологія

- Методи аналізу

- Міжнародне приватне право

- Міжнародний маркетинг

- Основи екології

- Предмет Політологія

- Соціальне страхування

- Технічні засоби організації дорожнього руху

- Товарознавство продовольчих товарів

Тлумачний словник

Авто

Автоматизація

Архітектура

Астрономія

Аудит

Біологія

Будівництво

Бухгалтерія

Винахідництво

Виробництво

Військова справа

Генетика

Географія

Геологія

Господарство

Держава

Дім

Екологія

Економетрика

Економіка

Електроніка

Журналістика та ЗМІ

Зв'язок

Іноземні мови

Інформатика

Історія

Комп'ютери

Креслення

Кулінарія

Культура

Лексикологія

Література

Логіка

Маркетинг

Математика

Машинобудування

Медицина

Менеджмент

Метали і Зварювання

Механіка

Мистецтво

Музика

Населення

Освіта

Охорона безпеки життя

Охорона Праці

Педагогіка

Політика

Право

Програмування

Промисловість

Психологія

Радіо

Регилия

Соціологія

Спорт

Стандартизація

Технології

Торгівля

Туризм

Фізика

Фізіологія

Філософія

Фінанси

Хімія

Юриспунденкция

LECTURE NINE

Plan

English Intonation, Its Structure, Function and Modal Meaning.

1. Structure of intonation.

2. Function of intonation.

3. Intonation of function words.

1. Structure and function of intonation. Intonation is a language universal. There are no languages which are spoken as a monotone, i.e. without any change of prosodic parameters, but intonation functions in various languages in a different way.

On perception level prosody['prɔsədɪ]is a complex formed by significant variations of pitch (висота), loudness, tempo and rhythm (i.e. the rate of speech and pausation) closely related. Some linguists regard speech timbre ['tæmbrə] as a component of intonation. There is an agreement between phoneticians that on perception level a complex unity formed by significant variations of 1) pitch, 2) loudness (force) and 3) tempo (i.e. the rate of speech and pausation) is called intonation. Thus, prosody and intonation relate to each other as a more general notion (prosody) and its part (intonation).

On the acousticlevel pitch correlates with the fundamental frequency of the vibration [vaɪ'breɪʃ(ə)n] of the vocal cords; loudness correlates with the amplitude of vibrations; tempo is a correlate of time during which a speech unit lasts.

Each syllable of the speech chain has a special pitch colouring. Some of the syllables have significant moves of tone up and down. Each syllable bears a definite amount of loudness. Pitch movements are inseparably connected with loudness. Together with the tempo of speech they form an intonation patternwhich is the basic unit of intonation.

An intonation pattern contains one nucleus and may contain other stressed or unstressed syllables normally preceding or following the nucleus. The boundaries of an intonation pattern may be marked by stops of phonation, that is temporal pauses.

Intonation patterns serve to actualize syntagms (ритміко-інтонаційні структури мовлення) in oral speech. The syntagm is a group of words which is semantically and syntactically complete. In phonetics actualized syntagms are called intonation groups.

Not all stressed syllables are of equal importance. One of the syllables has the greater prominence than the others and forms the nucleusof an intonation pattern. Formally, the nucleus may be described as a strongly stressed syllable which is generally the last strongly accented syllable of an intonation pattern and which marks a significant change of pitch direction, that is where the pitch goes distinctly up or down. The nuclear tone is the most important part of the intonation pattern without which the latter cannot exist at all. On the other hand, an intonation pattern may consist of one syllable, which is its nucleus. The most important nuclear tones in English are:

Low Fall − ˎNo

High Fall − ˋNo

Low Rise − ˊNo

High Rise − ˏNo

Fall-Rise − ˬNo

Rise-Fall − ˆNo

Mid Level − ›No

These tones are called kinetic or moving because the pitch the voice moves upwards or downwards, or first one and then the other, during the whole duration of the tone. There are also static tones, in which the voiceremains steady on a given pitch throughout the duration of the tone: the high level tone, the low level tone. Moreover, the pitch can change either in one direction only (a simple tone) or in more than one direction (a complex tone).

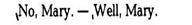

The meanings of the nuclear tones are difficult to specify in general terms. Roughly speaking, the falling tone of any level and range expresses "certainty", 'completeness', 'independence'. Thus, a straightforward statement normally ends with a falling tone since it asserts a fact of which the speaker is certain. It has an air of finality, e.g.

A rising tone of any level and range on the contrary expresses 'uncertainty', 'incompleteness' or 'dependence'. A general question, for instance, has a rising tone, as the speaker is uncertain of the truth of what he is asking about, e.g.

1. The English Low Fallin the nucleus starts somewhat higher than the mid level and usually reaches the lowest pitch level. It is represented graphically with a downward curve on the tonogram and its tone mark in the text is

1. The English Low Fallin the nucleus starts somewhat higher than the mid level and usually reaches the lowest pitch level. It is represented graphically with a downward curve on the tonogram and its tone mark in the text is

The use of the Low Fall enables the speaker to convey in his utterance an impression of neutral, calm finality, resoluteness. Phrases with the Low Fall sound categoric, calm, neutral, final.

2. The English High Fallin the nucleus starts very high and usually reaches the lowest pitch. The High Fall provides a great degree of prominence, which depends on the height of the fall. Its tone mark in the text is

2. The English High Fallin the nucleus starts very high and usually reaches the lowest pitch. The High Fall provides a great degree of prominence, which depends on the height of the fall. Its tone mark in the text is

The use of the High Fall adds personal concern, interest and warmth to the features characteristic of the Low Fall. The High Fall sounds lively, interested and airy in statements. It sounds very emotional and warm, too.

3. The English Low Rise in the nucleus starts from the lowest level and reaches the medium level (the nuclear variant). If the nucleus is followed by a tail, it is pronounced on the lowest level and the syllables of the tail rise gradually (the nuclear-post-nuclear variant). The two variants of the Low Rise (the nuclear and the nuclear-post-nuclear) are pronounced in a different way and consequently they have different graphical representations on the tonogram, but the same tone marks in the text.

The Low Rise conveys a feeling of non-finality, incompleteness, hesitation. Phrases pronounced with this tone sound not categoric, non-final, encouraging further conversation, wondering, mildly puzzled, soothing.

4. The English High Risein the nucleus rises from a medium to a high pitch, if there is no tail. If there are unstressed syllables following the nucleus, the latter is pronounced on a fairly high level pitch and the syllables of the tail rise gradually.

The High-Rise expresses the speaker's active searching for information. It is often used in echoed utterances, calling for repetition or additional information or with the intention to check if the information has been received correctly. Sometimes this tone is meant to keep the conversation going.

5. The Fall-Rise is called a compound tone as it actually may present a combination of two tones: either the Low Fall-Low Rise or the High Fall-Low Rise. The Low Fall-Rise may be spread over one, two or a number of syllables; the High Fall-Rise always occur on separate syllables.

If the Low Fall-Rise is spread over one syllables, the fall occurs on the first part of the vowel from a medium till a low pitch, the rise occurs on the second part of the vowel very low and does not go up too high: e. g. ↘↗No (the undivided variant).

If the fall and rise occur on different syllables, any syllables occurring between them are said on a very low pitch, notional words are stressed:

e. g. I ↘think his face is fa↗miliar (the divided variant)

The falling part marks the idea which the speaker wants to emphasize and the rising part marks the addition to this main idea.

The Fall-Rise is a highly implicatory tone. The speaker using this tone leaves something unsaid known both to him and his interlocutor. It is often used in statements and imperatives. Statements with the Fall-Rise express correction of what someone else has said or a contradiction to something previously said or a warning. Imperatives pronounced this way sound pleading. Greetings and leave-takings sound pleasant and friendly being pronounced with the Fall-Rise:

e. g. He is ↘thirty. – He is ↘thirty-↗five (a mild correction).

We’II ↘go there.–- You ↘↗shan't. (a contradiction).

I must be on ↘time. – ↘You'll be ↗late ( a warning).

It's all so ↘awful. – ↘Cheer ↗up. (pleading).

Goodnight, Betty. – ↘Good ↗night, Mrs. Sandford. (friendly).

6. The Rise-Fall is also a compound tone. In syllables pronounced with the Rise- Fall the voice first rises from a fairly low to a high pitch, and then quickly falls to a very low pitch; e. g.: Are you sure? – ↗↘Yes.

The Rise-Fall denotes that the speaker is deeply impressed (favorably or unfavorably). Actually, the Rise-Fall sometimes expresses the meaning of "even".

E.g.: You aren't ↗↘trying. (You aren't even trying).

This nuclear tone is used in statements and questions which sound impressed, challenging, imperatives pronounced this way sound hostile. E.g.:

Don't treat me like a baby. – Be ↗↘sensible then.

Has he proposed to her? - Why should you ↗↘worry about it?

Did you like it? – I simply ↗↘hated it.

I'm awfully sorry. – No ↗↘doubt. (But it's too late for apologies).

7. The Mid-Level tone in the nucleus is pronounced on the medium level with any following tail syllables on the same level. Its tone mark in the text is > and it is marked on the tonogram with a dash: –. The Mid-Level is usually used in non-final intonation groups expressing non-finality without any expression of expectancy, e.g.:

Couldn't you help me ? >At present | I'm too busy.

What did Tom say? >Naturally, | he was delighted.

The English dialogic speech is highly emotional, that's why such emphatic tones as the High Fall and the Fall-Rise prevail in it. It is interesting to note, that the most frequently occurring nuclear tone in English the Low Fall occupies the fourth place in dialogic speech after the High Fall, the Fall-Rise and the Low Rise.

The change in the pitch of the word which is most important semantically, is called a nuclear tone.Other words in the sentence also important for the meaning are stressed but their pitch remains unchanged.

The nucleusmay be preceded or followed by stressed and unstressed syllables. Stressed syllables preceding the nucleus together with the intervening unstressed syllables form the head of a tone unit. Initial unstressed syllables make the pre-head.Unstressed and half-stressed syllables following the nucleus are called the tail.

The tone of a nucleus determines the pitch of the rest of the intonation pattern following it which is called the tail. Thus after a falling tone, the rest of the intonation pattern is at a low pitch. After a rising tone the rest of the intonation pattern moves in an upward pitch direction:

The nucleus and the tail form what is called terminal tone.

The headand the pre-head form the pre-nuclear part of the intonation pattern and; like the tail, they may be looked upon as optional elements, e.g.

Usually a nucleus will be present in a tone unit; other elements may not be realized, i.e. the possibilities for combining the elements of a tone unit may be as follows:

| Pre-head | Head | Nucleus | Tail |

| 1. 2. 3. 4. I'll 5. I'll 6. I 7. I | What should I ask what to ask what to | Do. Do do? do do do do | something. about it. it. |

The pre-nuclear part can take a variety of pitch patterns. Variation within the prenucleus does not usually affect the grammatical meaning of the utterance, though it often conveys meanings associated with attitude or phonetic styles. There are three common types of pre-nucleus: a descending type in which the pitch gradually descends (often in 'steps') to the nucleus; an ascending type in which the syllables form an ascending sequence and a level type when all the syllables stay more or less on the same level. As the examples show, the different types of pre-nucleus do not affect the grammatical meaning of the sentence but they can convey something of the speaker's attitude.

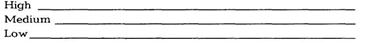

Variations in pitch range (мелодійних діапазонів) occur within the normal range of the human voice, i.e. within its upper and lower limits. Three pitch ranges are generally distinguished: normal, wide, narrow:

Pitch levels (мелодійні рівні) may be high, medium and low.

The meaning of the intonation group is the combination of the 'meaning' of the terminal tone and the pre-nuclear part combined with the 'meaning' of pitch range and pitch level.

2. Functions of intonation.Intonation is a powerful means of human intercommunication. One of the aims of communication is the exchange of information between people. The meaning of an English utterance derives not only from the grammatical structure, the lexical composition and the sound pattern. It also derives from variations of intonation. There is no general agreement about either the number or the headings of the functions of intonation. We'll follow David Crystal who in The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language offers the functions of intonation summarized as follows:

| Function | Its explanation |

| 1. Emotional | to express a wide range of attitudinal meanings – excitement, boredom, surprise, friendliness, reserve, etc. Here, intonation works along with other prosodic and paralinguistic features to provide the basis of all kinds of vocal emotional expression. |

| 2. Grammatical | to mark grammatical contrasts. Specific contrasts, such as question and statement, or positive and negative, may rely on intonation. Many languages make the important conversational distinction between ‘asking’ and ‘telling’ in this way, e.g. She’s here, isn’t she! (where a rising pitch is the spoken equivalent of the question mark) vs She’s here, isn’t she! (where a falling pitch expresses the exclamation mark). |

| 3. Information structure | to convey what is new and what is already known in the meaning of an utterance – what is referred to as the ‘information structure’ of the utterance. If someone says I saw a BLUE car, with maximumintonational prominence on blue, this presupposes that someone has previously asked about the colour; whereas if the emphasis is on I, it presupposes a previous question about which person is involved. It would be very odd for someone to ask Who saw a blue car!, and for the reply to be: I saw a blue car! |

| 4. Textual | to construct larger than an utterance stretches of discourse. Prosodic coherence is well illustrated in the way paragraphs of information are given a distinctive melodic shape, e.g. in radio news-reading. As the news-reader moves from one item of news to the next, the pitch level jumps up, then gradually descends, until by the end of the item the voice reaches a relatively low level. |

| 5. Psychological | to organize language into units that are more easily perceived andmemorized. Learning a long sequence of numbers, for example, proveseasier if the sequence is divided into rhythmical ‘chunks’. |

| 6. Indexical (дейктична) | to serve as markers of personal identity – an ‘indexical’ function. Inparticular, they help to identify people as belonging to different socialgroups and occupations (such as preachers, street vendors, armysergeants). |

The communicative function of intonation is realized in various ways thatcan be grouped under five general headings. Intonationserves:

1. To structure the information contentof a textual unit so as to show which information is new or cannot be taken for granted, as against information which the listener is assumed to possess or to be able to acquire from the context, that is given information.

2. To determine the speech functionof a phrase, i.e. to indicate whether it is intended as a statement, question, command, etc.

3. To convey connotational meanings of 'attitude'such as surprise, annoyance, enthusiasm, involvement, etc. This can include whether meaning are intended, over and above the meanings conveyed by the lexical items and the grammatical structure.

4. To structure a text.Intonation is an organizing mechanism. On the one hand, it delimitatestexts into smaller units, i.e. phonetic passages, phrases and intonation groups, on the other hand, it integrates these smaller constituents forming a complete text.

5. To differentiatethe meaning of textual units(i.e. intonation groups, phrases and sometimes phonetic passages) of the same grammatical structure and the same lexical composition, which is the distinctive or phonological function of intonation.

6. To characterize a particular style or variety of oral speech that may be called the stylisticfunction.

In oral English the smallest piece of information is associated with an intonation group, that is a unit of intonation containing the nucleus.

There is no exact match between punctuation in writing and intonation groups in speech. Speech is more variable in its structuring of information than writing. Cutting up speech into intonation groups depends on such things as the speed at which you are speaking, what emphasis you want to give to the parts of the message, and the length of grammatical units. A single phrase may have one intonation group; but when the length of phrase goes beyond a certain point (say roughly ten words), it is difficult not to split it into two or more separate pieces of information, e.g.

The man told us we could park it here.

The man told us | we could park it at the railway station.

The man told us | we could park it | in the street over there.

Accentual systems involve more than singling out important words by accenting them. Intonation group or phrase accentuation focuses on the nucleus of these intonation units. The nucleus marks the focus of information or the part of the pattern to which the speaker especially draws the hearer's attention. The focus of information may be concentrated on a single word or spread over a group of words.

Out of the possible positions of the nucleus in an intonation group, there is one position which is normal or unmarked, while the other positions give a special or marked effect. In the example: 'He's gone to the office' the nucleus in an unmarked position would occur on 'office'. The general rule is that, in the unmarked case, the nucleus falls on the last lexical item of the intonation group and is called the end focus. In this case sentence stress is normal. But there are cases when you may shift the nucleus to an earlier part of the intonation group. It happens when you want to draw attention to an earlier part of the intonation group, usually to contrast it with something already mentioned, or understood in the context. In the marked position we call the nucleus contrastive focus or logical sentence stress, e.g.:

'Did your brother study in Kyiv?' "̖No, he was born in Kyiv.'

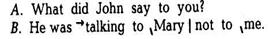

In this example contrastive meaning is signaled by the falling tone and the increase of loudness on the word born. Sometimes there may be a double contrast in the phrase, each contrast indicated by its own nucleus:

Her ̖mother | is ̖Ukrainian | but her ̖father | is ̖German.

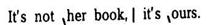

In a marked position, the nuclei may be on any word in an intonation group or a phrase. Even words like personal pronouns, prepositions and auxiliaries, which are not normally stressed at all, can receive nuclear stress for special contrastive purposes:

The widening of the range of pitch of the nucleus, the increase of the degree of loudness of the syllable, the slowing down of the tempo make sentence accent emphatic:

We can roughly divide the information in a message into given information(or the theme) and new information (or the rheme). Given information is something that the speaker assumes the hearer knows about already. New information can be regarded as something that the speaker does not assume the hearer knows about already.

In the response 'He was talking' is given information; it is already given by the preceding clause; 'not to me' conveys new information. A new information is obviously what is most important in a message, it receives the information focus, in the nucleus, whereas old information does not.

By putting the stress on one particular word, the speaker shows, first, that he is treating that word as the carrier of new, non-retrievable information, and, second, that the information of the other, non-emphasized, words in the intonation group is not new but can be retrieved from the context. 'Context' here is to be taken in a very broad sense: it may include something that has already been said, but it may include only something (or someone) present in the situation, and it may even refer, very vaguely, to some aspect of shared knowledge which the addressee is thought to be aware of. The information that the listener needs in order to interpret the sentence may therefore be retrievable either from something already mentioned, or from the general 'context of situation'.

Degrees of information are relevant not only to the position of sentence stress but also to the choice of the nuclear tone. We tend to use a falling tone of wide range of pitch combined with a greater degree of loudness, that is emphatic stress, to give emphasis to the main information in a phrase. To give subsidiary or less important information, i.e. information which is more predictable from the context or situation, the rising or level nuclear tone is used.

5. Intonation of function words. In a sentence or an intonation group some words are of greater importance than the others. Words which provide most of the information are called content/notional words; function/structure/form words are those words which do not carry so much information.

Content words are brought out in speech by means of sentence-stress (or utteггапсе-level stress). Sentence stress/utterance-levelstress is a special prominence given to one or more words according to their relative importance in a sentence/utterance.

Stress, i.e. prosodic highlighting, is related in a very important way to information. In languages, prosodic highlighting serves a very obvious deictic function which is tosignal important information for the listeners.

Under normal conditions, it is the content words (nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs) that are accentuated by pitch, length, loudness or a combination of these prosodic features. Function words (prepositions, articles, pronouns) and affixes (suffixes and prefixes) are de-emphasized or backgrounded informationally by destressing them.

When any word receiving stress has more than one syllable, it is only the word's most strongly stressed syllable that carries the sentence stress.

Look at this telegram message: Arriving Kennedy airport Tues 03.45 p.m. This is not a complete sentence, but the words carry the important information; they are all content words are emphasized by sentence stress: nouns, adjectives, verbs (with the exception of link verbs, auxiliary verbs and modal verbs), numerals, adverbs, demonstrative, interrogative pronouns, etc. Let us expand the message: I am ARRIVING KENNEDY AIRPORT on TUESDAY 03.45. Articles, prepositions, conjunctions, personal pronouns, possessive pronouns, etc, arenot normally emphasized. As a matter of fact, they can be pronounced in two differentways: in their strong (stressed) form and in their weak (reduced, unstressed) form. It isimportant to know when these forms can and cannot be used.

Function wordsusually have strong forms when they are:

1. at the end of the sentence, e.g.: What are you looking at? Where are you from? I’d love to.

2. used for emphasis, e.g.: Do you want this one? No. Well, which one do you want? That one.

3. used for contrast, He is working so hard. She is but not he.

In ordinary, rapid speech such words can occur much more frequently in their weak form than in their strong form. Because they are unstressed in the stream of speech, function words exhibit various forms of reduction, including the following:

1. the weakening or centralizing of the internal vowel to [ə], e.g.: must [məst]. In certain phonetic environments, e.g. where syllabic consonants are possible, the reduction of a short vowel + consonant sequence to a syllabic consonant [ænd] → [n], as in the example of bread and butter, fish and chips, etc. Sometimes the unstressed internal vowel can fall out completely, e.g. from [frəm] → [frm], [fm]

2. loss of an initial consonant sound, e.g. them [ðəm] → [əm], his [hiz] → [iz];

3. loss of a final consonant, e.g. and [ənd] → [ən], of [ɔv] → [ə].

In fact, function words cause problems for the nonnative listeners since in their most highly reduced form, the pronunciation forms for many common function words are virtually identical, e.g.: a, have, of → [ə].

6. Sentence stress. The main function of sentence stress is to single out the focus/the communicative centre of the sentence which introduces new information.

Within a sentence/an intonation unit, there may be several words receiving sentence stress but only one main idea or prominent element. Speakers choose what information they want to highlight in an utterance/sentence. The stressed word in a given sentence which the speaker wishes to highlight receives prominence and is referred to as the (information) focus/the semantic center.

In unmarked utterances, it is the stressed syllable in the last content word that tends to exhibit prominence and is the focus. When a conversation begins, the focus /the semantic center is usually on the last contentword, e.g. Give me a HELP. What's the MATTER? What are you DOING? Words in a sentence can express new information (i.e. something mentioned for the first time/rheme/comment) or old information (i,e. something mentioned or referred to before/theme/topic). Within an intonation unit/sentence, words expressing old or given information (i.e. semantically predictable information) are unstressed and are spoken with lower pitch, whereas words expressing new information are spoken with strong stress and higher pitch. Here is an example of how prominence marks newversus old information. Capital letters signal new information (strong stress and high pitch):

A: I've lost my HAT. (basic stress pattern: the last content word receives prominence)

В: What KIND of hat1? ('hat' is now old information; 'kind' is new information)

A: It was a SUN hat.

В: What COLOR sun hat?

A: It was YELLOW. Yellow with STRIPES.

В: There was a yellow hat with stripes in the CAR.

A: WHICH car?

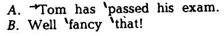

The speaker can give focus/prominence to words to contrast information,i.e. to correct or check it. Words which are given prominence tocontrast information have contrastive stress, e.g.:

1 A: Have they ever visited LONDON?

В: No, THEY haven't, but their SON has. (correcting information)

2 A: I didn't LIKE the movie.

В: You didn't LIKE? (checking information)

The speaker can wish to place special emphasis on a particular element – emphatic stress. The element receiving emphatic stress usually communicates new informationwithin sentence. It is differentiated from normal focus/prominence by the greater degreeof emphasis placed on it by the speaker, e.g.:

A: How do you like the new courses you've taken this semester?

В: I'm REALLY enjoying them! (emphatic stress on really indicates a strong degree enjoyment)

A: I'm NEVER eating oysters again! (emphatic stress placed on never signals a particularly bad reaction the speaker once had when eating oysters)

English has certain anaphoric wordswhose function is to refer to what has previously and recently) been communicated in a different way. Since anaphoric words contain no new information – in fact, are intended to repeat old information – they typically not accented.

A summarized list of anaphoric wordscan be given as follows:

1. The pronouns he, she, it,and they,which replace definite nouns and noun phrases, e.g.

Everybody likes Archibald. – Everybody likes him.

I was sitting behind Lisa. – 1 was sitting behind her.

We waited for our friends. – We waited for them.

2. The pronouns oneand some,which replace indefinite noun phrases, e.g.:

I'll lend you some money. – I'll lend you some.

She ordered a cake. – She ordered one.

3. The pronoun one, ones, which replaces nouns after certain modifiers, e.g.:

Are you wearing your brownsuit /or the blue one?

Is she wearing her brown shoes /or the black ones?

4. The words so and not,which replace clauses after certain verbs and adjectives, e.g.:

Has she failed to do it? – I hope not, but I'm afraid so.

5. The adverbs thereand then, which replace place phrases and time phrases, respectively, e.g.:

Have you ever been to Maplewood? I used to live there.

Next Monday's a holiday. I think I'll rest then.

6. The auxiliary do,which replaces a whole verb phrase, e.g.:

Who made all this mess. – I did.

When an anaphoric word is accented, the accent signals contrast or something special, e.g.:

Do you know Mary and John? I know her.

In addition to the cases listed above, we can recall old information by using words, which in a different context, would present new information. Such lexical items are deaccented, and the de-accenting tells us that the lexical items are being used anaphorically. There are several kinds of lexical anaphora:

1. Repetition, e.g. I've got a job,/ but I don't likethe job.

2. How many times? Threetimes.

3. Synonyms, e.g. Maybe this man can give us directions. I'll askthe fellow. (the fellow = the man)

4. Superordinate terms, e.g. Didyou enjoy Blue Highways?‒ I haven't read the book (Blue Highways = the book).

This wrench is no good.I need a bigger tool, (wrench = tool) The purpose of de-accenting in this case is to relate the more general term ‒ the book and tool, in these examples, to the more specific term of the preceding sentence. But the de-accented word or term does not necessarily refer directly to a previous term, e.g.:

That's a nice looking cake. Havea piece. But it must be de-accented.De-accenting also occurs when a word is repeated, even though it has a differentreferent the second time, e.g.: a room with a view and withouta view, deeds and misdeeds, written and unwritten. De-accenting can be used for a very subtle form of communication – to embed anadditional meaning,e.g. What did you say to Roger? I didn't speakto the idiot. The last sentence actually conveys two meanings, one embedded in the other: I didn't speak to Roger', and I call Roger an idiot'. De-accenting the idiot is equivalent to saying:the referent for this phrase is the same as the last noun that fits. In sum, sentence stress/utterance-level stresshelps the speaker emphasize the most significant information in his or her message.

Answer the questions:

1. Define prosody.

2. Define intonation pattern.

3. What is nucleus?

4. Characterize each of the nuclear tones in English. What are their meanings? What do they express?

5. Characterize the level nuclear tone.

6. What are the components of the intonation pattern in English?

7. What are the types of pre-nucleus?

8. What pitch levels are there in English?

9. What functions of intonation are distinguished by D. Crystal?

10. How is the communicative function of intonation realized?

11. Define logical sentence stress.

12. What are the terms for the given and the new information?

13. How can you prove that intonation transmits feelings and / or emotions?

14. What is the grammatical function of intonation?

15. How is the distinctive function of intonation realized?

16. What is the semantic centre of an utterance?

17. What are content/notional words and function/structure/form words?

18. What are words highlighted in an utterance with?

19. Define sentence stress/utterance-level stress?

20. What is its main function ? What does deictic mean?

21. What are means of this accentuation ?

22. Discuss cases when function words are used in their strong and weak forms.

23. What do function words exhibit in their weak forms?

24. What is the sentence focus and where is it located in unmarked utterances?

25. How can a speaker place special emphasis on a particular element in an utterance?

26. What are anaphoric words? What is their function? Give examples.

27. What is de-accenting? What are its means and function?

28. How would you define the role of sentence stress/utterance-level stress?

Література: [2, с. 147-191; 4, c. 83-101].

Читайте також:

- BASIC NOTIONS OF THE LECTURE.

- BASIC NOTIONS OF THE LECTURE.

- LECTURE 1. Contrastive Stylistic as a Linguistic Discipline

- Lecture 12. Evolution of the ME Lexical System.

- LECTURE 13

- Lecture 14. Evolution of the ME Nominal Morphology.

- Lecture 16

- Lecture 16

- Lecture 4

- LECTURE EIGHT

- LECTURE ELEVEN

- LECTURE FIVE

| <== попередня сторінка | | | наступна сторінка ==> |

| LECTURE EIGHT | | |

|

Не знайшли потрібну інформацію? Скористайтесь пошуком google: |

© studopedia.com.ua При використанні або копіюванні матеріалів пряме посилання на сайт обов'язкове. |